Decision rights – who can make decisions about what – are an important element of any organization. Clear rights ensure that matters such as legitimacy and authority are widely understood in a shared way horizontally and vertically. On the opposite end of the spectrum, a lack of clarity in this regard can lead to all sorts of organizational disruption as individuals grapple with how they relate to the decision-making process and to the decisions that come out of them. Bartling and colleagues found, in fact, that this matter is intrinsically important to individuals and should inform how we manage, govern, and design jobs. Just think about when we don’t have clear roles and rights defined. We all have asked at one time or another questions like:

- why wasn’t I consulted on that?

- what is in my purview to do and when do I need to ask permission – or forgiveness ;)?

- who is that person/role to make that decision?

- do I have to follow that person’s instruction if they aren’t my supervisor?

I’ve had the unmitigated joy of working with Jessica Sabbagh, a change and management practitioner, over the last two years to codify decision processes and rights in an institution of higher education. Jessica brought her practice from other organizations, particularly the RAPID framework that is process oriented, while I blended in my own experience with the RACI framework that is role oriented. Together, these frameworks have helped establish processes and roles for numerous large-scale changes at the institution. In this post, I’ll share a bit about each of these tools and how we’ve applied them to particular projects.

Don’t miss the resources section, too! I’ve loaded it with some really good research on why you’d want to work on this intentionally and plenty of links to resources on how/what.

Role Clarity: RACI

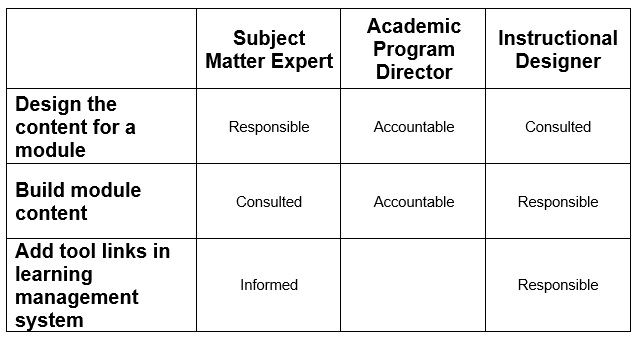

Acknowledging that there are lots of other resources on the frameworks I’ll introduce, I will keep these descriptions short. RACI is an acroynm for Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed. The idea is to create a matrix of the things to be done and the people / roles in the organization. Where a role and a task intersect, you denote which status – R, A, C, or I – is appropriate. When none of these statuses apply, you’d leave the cell blank. The most common question I get when introducing RACI to a group is, “what’s the difference between responsible and accountable?” The easiest way to think about this is in terms of who does the work (responsible) and who determines if the work was done to standard (accountable)? The accountable party is where the buck stops. Motion has a really great article if you want to read more about the details.

Below is a very basic example, too, from a domain that I’m familiar with – instructional design projects – that may help you contextualize to higher ed. Here, the academic program director oversees the whole project of delivering a well-designed course, so they are accountable for the core activities. The subject matter expert (or faculty member, depending upon your context) designs the content and assessments, while the instructional designer helps with that activity and then translates the product into the learning management system (LMS). The third task – adding tool links to the LMS – is a good example of when someone may only be informed of the outcome, while another party in the matrix (program director) has no specific role. In this case, the accountable party for tool installation in the LMS likely would fall to another party not on the matrix, namely the instructional designer’s supervisor or maybe a system administrator in information technology.

The major benefit I’ve seen come from using RACI is that everyone knows how everyone else fits into the overall work to be done. Clear swim lanes helps people know what they should be doing, what they have latitude to address in their own way, when they need to defer to or consult with someone, who is going to evaluate their work output, etc. So, if you find yourself in a situation where folks are stepping on one another’s toes on a regular basis, you just might benefit from sitting down to chart out a RACI matrix together so that you can arrive at a shared understanding of roles.

Process Clarity: RAPID

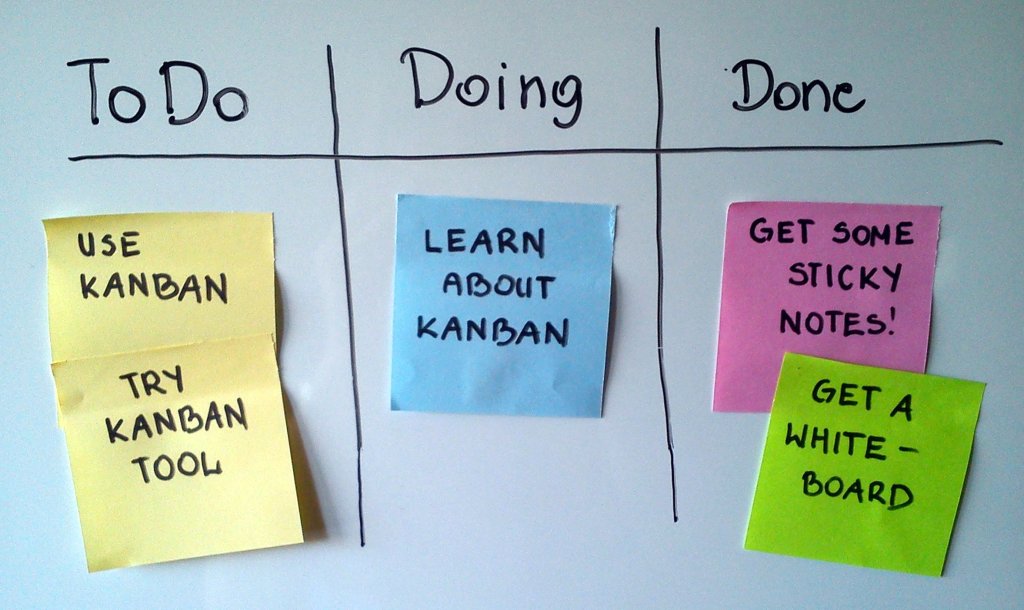

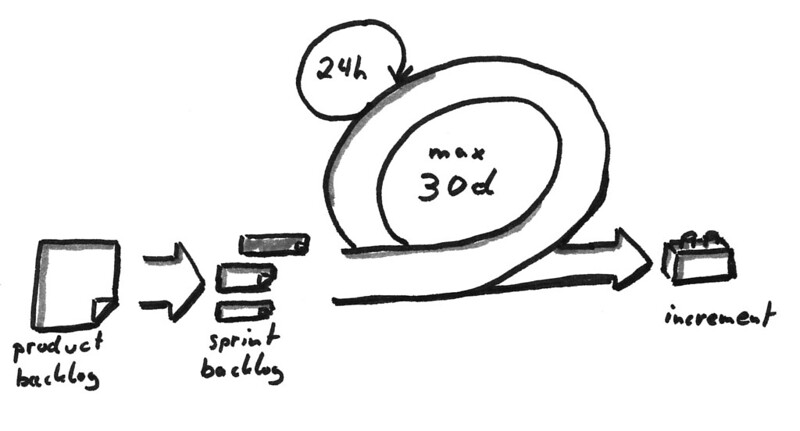

RAPID, on the other hand, is primarily about a process for making decisions. The acronym stands for recommend, approve, perform, input, decide. Below is a flowchart demonstrating the way that a decision gets put together, starting with gathering input from appropriate constituents all the way to performing the outcome of the decision. Most of the questions I get about RAPID relate to the “approve” step. A couple of points, there: (1) there isn’t always someone(s) who holds this responsibility in any given process, and (2) this stage can be thought of as fulfilling a couple core functions: helping the recommender put together the best possible recommendation – a sounding board, i.e. – and vetoing a recommendation that will not work. Approvers often align to legal, regulatory, accreditation, and financial functions at the organization – the controls in the system, i.e.

Another key area of learning I’ve had about RAPID relates to the “input” step. The first thing to keep in mind is that the breadth of voices being collected is going to relate pretty closely to the “consulted” status in RACI. So, if you’re using both tools, you can go to your RACI matrix as a first step in identifying who should be giving input. It’s also a good idea to go to your team or your counselors to consider who else may need to provide input to get the best possible recommendation. Shifting to the process itself, it’s also critically important to be transparent with folks at the input stage. They need to understand that they are (typically) one of many roles to provide feedback and that the recommender will weave everyone’s thoughts into the best possible recommendation. That often means that not every idea or every constituent’s points of view will end up in the recommendation. And that’s okay; it’s to be expected.

My final point to share on RAPID before we transition to some examples is that there is a huge opportunity for the decider to provide a clear charge and evaluative criteria at the outset. These formalizations will help everyone in the process understand what the target is and get comfortable with how and why a decision is being made. Conversely, not knowing these elements can cause a stall out at the decision step – the decider may ask for more data or may ask to go back to other folks who did not originally give input, etc. – or may lead to more subjective decisions rather than objective evaluations of recommendations. Both of these kinds of outcomes confuse decision rights rather than deliver the clarity that folks desire. For much more detail on RAPID, the Bridgespan Group has a fantastic article.

Example: Aligned Academic Calendars

One project where we deployed RACI and RAPID together was in a years-long process to align several academic calendars at our institution. We had long understood RACI statuses for a stable environment as it relates to our calendars. The registrar’s office was responsible for charting out the calendars; the senior-most academic leader is accountable; faculty, program directors, financial aid, the bursars office, advising, marketing, admissions, and some other key student-facing functions are consulted parties; and the whole community is informed.

When it came time to consider making a change in the calendar, it made sense to review the RACI roles and start to map them into the RAPID process. All of the consulted parties now had input; the registrar, as responsible party, was the recommender; finance and financial aid were approvers given the importance of Title IV regulations and award periods; the chief academic officer, as accountable party, was the decider; and the performing party was the registrar in concert with academic program directors, advising, financial aid, marketing, and all of the other constituents who had to carry out communications or systems changes.

Having roles clearly established ahead of time made it much easier to engage in the RAPID process. People knew intuitively where they fit into the decision. This speaks to the benefit of undertaking a RACI-type discussion at the front end of any decision or change to be initiated through RAPID.

Example: KPIs

An example that was a little more ad hoc in the way it unfolded was setting institutional KPIs and aligned leading indicators. While the institution had tried KPIs at the board level many years ago, the concept never took hold and was not brought to the wider organization. That meant that the work to establish internally facing KPIs, albeit that would be shared with the board, was a new task and concept. There was no RACI matrix to go back to, in other words. Working with a core team, one of our first tasks was to chart out the roles for senior leaders, the executive team, the president, the board, and faculty and staff. The hierarchical nature meant that RACI statuses cascaded. For example, the board has ultimate accountability for the performance of the KPIs, but the president also holds the executive team accountable, and they the senior leaders, so on and so forth.

Once we sketched out the RACI matrix, though, it became much easier to figure out the assignment of placements in the RAPID framework. The executive team would provide input; the VP of learning innovation, analytics, and technology (he is I) would be the recommender since I was the assigned project lead/sponsor; there was no approver in this case; the president was decider #1; the board was decider #2 (yes, it’s okay to have a longer chain); and then the whole organization had roles in performing. Analytics and IT built the report and data feeds, senior leaders provided input on leading metrics, executive members set goals, etc., etc.

What was amazing to me was that we were able to do this process, at least defining and capturing, in under three months. The much longer conversation has been around setting goals and benchmarks and establishing the leading indicators. Still, it was pretty remarkable what was possible once everyone knew their roles and knew how the process was going to unfold.

Closing Thoughts

Through these examples, I have come to liken the pairing of these two tools to having a compass (RACI) and a map (RAPID) to get you to the destination. Each is useful in its own right, but the most successful projects will have both role and process clarity. The end result is a delivered decision or change where the constituents understand the decision rights from the beginning, there is transparency around the process and product, and a greater level of buy-in at the end. You could do a change without this, but why would you 😉

References & Resources

Bartling, Fehr, & Herz (2014). The intrinsic value of decision rights.

Bridgespan Group. The RAPID decision-making tool for nonprofits.

Miranda & Watts (2022). What is a RACI chart? How this project management tool can boost your productivity.

Motion. RACI responsible vs. accountable: Key concepts defined.

Rogers & Blenko (2006). Who has the D?: How clear decision roles enhance organizational performance.

The Holdsworth Center. Let’s be clear: There’s a tool for decision-making that can change your life.

Bonus – RACI may not work in your environment; we’ve talked about using a different but very similar tool: DARE. McKinsey sets out a good case for when RACI may not work and why DARE may be better.

Leave a comment